2023 | 7 min read

False memory syndrome occurs when a person imagines events they didn’t actually experience. As a psychological disorder, it usually refers to something traumatic, such as remembering abuse that never occurred. I wonder if false memory syndrome might also be related to places or environments, such as identifying too strongly with another culture. Doesn’t living in Tokyo implant a little false memory of its own?

Take Showa pop. I’ll be minding my own business at the supermarket when I hear it, wafting up between announcements for a price-down campaign on fresh salmon. I’m talking about the supermarket song. That nostalgic melody that takes up permanent residence in your brain. Thirty seconds of praise for the supermarket’s role in daily life, sung with coquettish gusto by two elder sisters who never quite made it to the top. One hand holding a pack of frozen gyoza, a lump forms in my throat.

The Showa period was a great time for me. Trips in the Nissan Bluebird and the ferry ride to Shikoku. Father’s company was going big guns in America and we were the first family in the neighbourhood to own a VCR. Mother wore cashmere everyday. The price of frozen gyoza was the same. We didn’t need phones, we had pagers! Somehow, I experienced all this while growing up in England. Call it borrowed nostalgia. It seems you can spend long enough in a place to eventually become attuned to its memories.

But nostalgic feelings aren’t the same as a full-spectrum cultural memory. So I couldn’t tell you if that 30-second ditty is based on an actual hit song from the Showa period, or if it was written and recorded by an ad agency for its supermarket client. Either way, I know I have a new favourite supermarket, I mean song. I’ll add it to my mental repository of Showa pop.

Showa pop, also known as kayōkyoku (literally, “pop songs”), is Japan’s mainstream popular music of the postwar period through to 1989. Showa pop trades in smalltown drama and the tribulations of boy-girl romance. For the girls, it’s all about finding the one. For the guys, a certain amount of philandering is expected. The ultimate fate of a Showa idol is to retire early and become a stay-at-home mother for the sake of her husband’s career. Yes, it’s that conservative. But shifts in music style kept it relevant over the years. Older Showa pop often comes in Hawaiian and rockabilly flavours. Later Showa pop imported Motown and disco sounds, without shedding its essential Japanese-ness.

Most Japanese music is composed on pentatonic scales, which omit two notes from the heptatonic, or seven-note, western scale. I’m no musicologist, but fewer notes means wider intervals, and this may explain why Japanese music can sound overreaching to western ears. I often heard those distinctive intervals as emotionally keening or pointlessly frantic. It takes a while for Japanese music to grow on you, or for you to grow on it, so that its emotional punches can land. Welling up at Showa pop – or its version upgrade, J-Pop – is a sign that you’re slowly being rewired. Unless you’re living in Japan, you’re unlikely to hear much Showa pop. What you will have heard though, is city pop.

City pop is a genre so perfectly packaged for global consumption that it’s amazing it was unknown for so long. True, city pop was sung mainly in Japanese, but it expressed a cosmopolitan yearning that went beyond words. City pop’s true home was Tokyo, but it sounded great anywhere there were night lights, an urban airport, or a beach within driving distance. If city pop had a natural home outside Japan, it was surely Los Angeles. Just like LA, city pop rejected authenticity and was always about the possibilities. That’s the message anyway from Yasuko Agawa’s 1986 slow-groove classic LA Night:

Just got in from Tokyo

(LA night, don't you wanna treat it right)

Tell me cab driver, where is there to go

(LA night, don't you wanna treat it right)

But this is just one definition of city pop. It turns out there are many. Trying to follow the term city pop down the decades is like trying to catch an electric eel in Tokyo Bay. In fact, the more popular city pop became, the less certain you could be what it was.

One purist definition of city pop applies only to the music of one band: the legendary but short-lived Happy End. Formed in Tokyo in 1969, Happy End took ideas from US west-coast rock and added Japanese lyrics. They weren’t the first rock group to sing in Japanese, but they were the first to do it with real panache. Their songs, which were sometimes sung-spoken, could sound languid or bitter, soulful or surreal, and often all of these at once. Happy End recorded three albums and departed the stage with a best-of album, City, in 1973. The four members then pursued solo careers and played backing for other artists as a session group called Caramel Mama. Taken together, these recordings form something like the holy scriptures of city pop, at least according to some.

That definition quickly falls apart when you look at music grouped and sold as city pop over the years. In the 1980s, city pop became shorthand for western-style soft rock that was jazzy in influence and exploited new studio technology, not always with great results. Most of this music was considered commercial or even cheesy at the time. The style is epitomised by “King of City Pop” Tatsuro Yamashita, whose music has all the urban sophistication of Phil Collins singing to a parking meter.

By the time of the great city pop revival of the 2010s, the cheesier stuff had been edited out to create a more marketable genre that looked and sounded great on playlists. City pop now meant mostly solo female Japanese artists like Mariya Takeuchi and Miki Matsubara, who sang in a soul, disco (the more on-trend term is “boogie”) or otherwise urban style. Not that the style really mattered. City pop was becoming a purely aesthetic label. You knew it when you heard it, or even just saw it. Rolling Stone got it right when it called city pop less of a genre and more of a vibe.

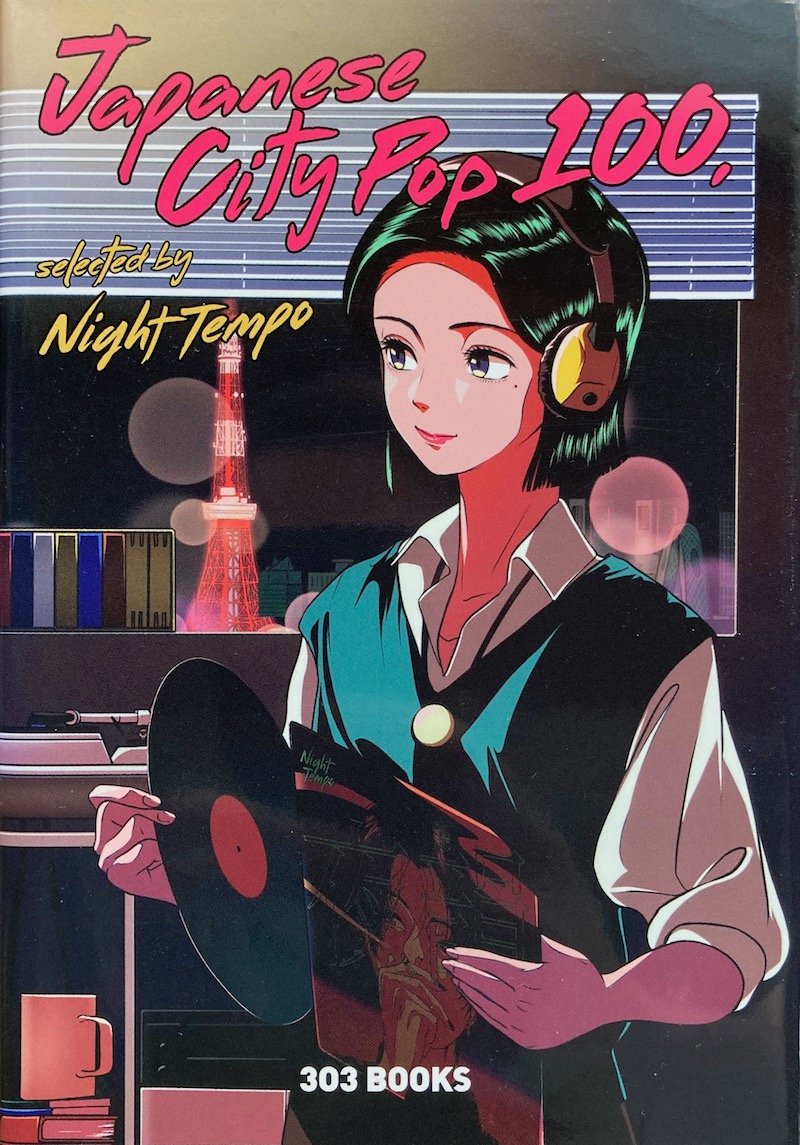

This vibe travelled unexpectedly well outside Japan. The book and presumed taste-bible Japanese City Pop 100, as selected by Korean DJ and producer Night Tempo, is essentially a complete guide to sexy Japanese solo female artists of the 1980s. There’s no real attempt to define city pop as a genre, but by classifying 100 songs according to mood, Night Tempo provides a useful guide to the vibe. His nine moods of city pop are: Sweet Sorrow, Bright, Adult, Night, Love, Drive, Disco, Summer, Youth.

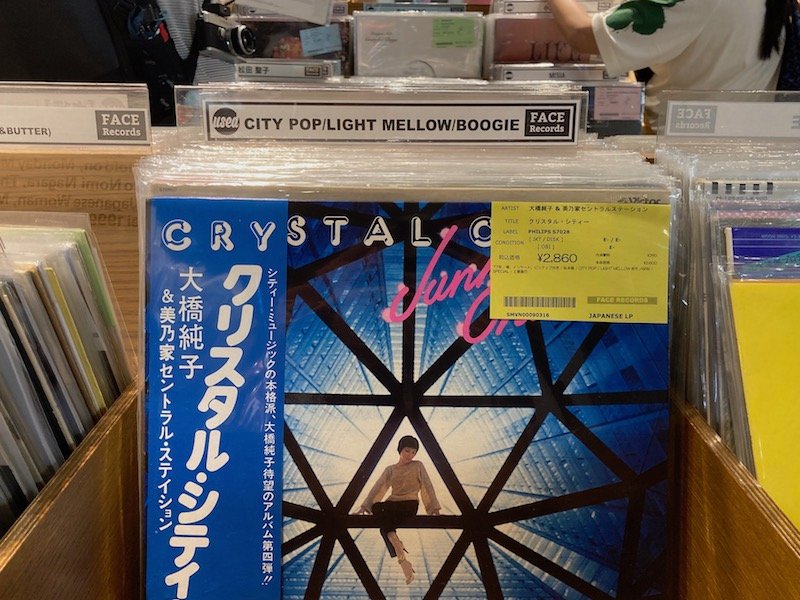

For a global audience, Japanese city pop came drenched in nostalgia and could only be understood as a series of moods. That uncertainty percolated back to Japan, where city pop would once have conjured up certain artists like Happy End, or later Tatsuro Yamashita. Go looking for city pop at Shibuya’s Face Records and you’ll find it conflated with light mellow and boogie, city-pop-adjacent genres that correspond to soft rock and disco. A separate categorisation would be problematic. It’s no longer possible to say exactly what city pop is.

Then again, city pop has always been a shape-shifter. Viewed historically, the label city pop was never actually used that much. In its first decade, it was synonymous with the New Music that emerged around 1970, led by the band Happy End. And this is where things get interesting. City pop was an antithesis. It stood for everything that Showa pop was not. Showa pop upheld family values; city pop was strictly about the individual. Showa pop was heard on the TV or radio; city pop was played on the car stereo. Showa pop was light entertainment; city pop was not.

The clue is in the word “city” itself. In 1970, Tokyo had just given birth to a new social fabric, one that remains a dominant feature of the city today. It was made up of young, mostly single people who were culturally omnivorous and had disposable income, but valued freedom more than money. Unlike the machi, or town, which was defined by relationships and cooperation, the city was a place of individuals. The music of Happy End was all about making sense of that new world you entered when family and community were stripped away. Even the name Happy End was an ironic take on the mainstream ideal of romance leading to marriage. As in Magazine House’s imminent invention of the city boy and city girl, city pop was always about the pursuit of happiness on your own terms.

Whether you first heard city pop in your Seoul bedroom, your Melbourne apartment or your London suburb, it’s no surprise that you recognised something in its mood. You didn’t understand the lyrics, but you knew what they were trying to say. You were listening to an individual making his, or more likely her, way in the world. You heard the crisp, elegant unboxing of a new identity in a new city. The lack of concern for authenticity was even part of the appeal. Maybe later you experienced a queasy nostalgia for summers you never lived, dates you weren’t on, night drives you hadn’t taken.

Next: Stationery Wonderland