2023 | 9 min read

Azabudai Hills is many things. It’s a modern urban village brimming with nature. It’s a compact city that brings together an attractive range of urban amenities. It’s a nature-rich town square. It’s a verdant urban oasis. The red and white cranes of the Shimizu Corporation had performed a miracle by lifting this lush green citadel 100 metres, then 200 metres, then 300 metres, vertically into the sky. They finally stopped at 330 metres, just three short of the nearby Tokyo Tower, a magnificent show of respect to a creaky 20th Century icon that brought a warm glow to the entire city.

The Mori Building Company and its PR agents then went to work cranking up the anticipation ahead of the grand opening on November 24th, 2023. On the morning of that felicitous day, the site in Tokyo’s inner Minato Ward was buzzing with a large crowd of curious Tokyoites. But at exactly eight minutes past ten, the spell was rudely broken. Standing in line with his mother, a young schoolboy whose insolence knew no bounds raised a stubby finger to the sky and said: “Look, it’s a huge glass tower!”

“Hans, no!” said the mother, covering the boy’s mouth, but the damage was done. Other people who were standing nearby and had heard everything shuffled their feet, turned this way and that, huffed into the cold autumn air, and did everything possible to distance themselves from the child. “Imagine bringing a kid to a place like this,” muttered one. “That mother’s certainly got her hands full,” opined another. “Hans?” said another.

Hans had seen the emerald city and it wasn’t verdant. It was an office tower attached to a patch of strategically greened space, just like all the others. Whether you’re a resident of Tokyo or someone who just loves this vast and ugly-beautiful pixellated city, you’ve probably felt something similar in the past. Hans is all of us. We are all witness to the incessant march of corporate-led urbanism as it goes about its business of furnishing Tokyo with an armada of glass towers called Hills, Gardens, Plazas and Squares.

Azabudai Hills, a skyscraper cluster that wants to be a nature-rich town square, is merely joining all the others such as Roppongi Hills, Toranomon Hills, Atago Green Hills, Hiroo Garden Hills, Tokyo Garden Square, Ebisu Garden Place, Tokyo Garden Terrace Kioicho, Harumi Triton Square, Tokyo Midtown, Izumi Garden Tower, Tokyu Plaza Ginza, and so on. It’s one more addition to the imaginary greenscape that exists mainly in the naming conventions of real-estate developments.

Despite the city’s outward appearance of a broiling concrete disarray, this imaginary Tokyo is an experiment in urban greening and good citizenship. In fact, citizens and private development corporations have never been further apart when it comes to the future direction of Tokyo. Citizens are generally dismayed by the corporate takeover of public space, while corporate urban planners appear sincere in their belief that building more skyscrapers can help to green the city. This sublime act of doublethink even has a name: the Vertical Garden City.

The Vertical Garden City is the simulation of nature in disaster-proof, in other words nature-proof, ultra-high-rise towers. While the original garden city proposed by Ebenezer Howard was surrounded by nature, the Vertical Garden City is programmed with a distinctly Japanese form of nature appreciation. The garden is meant to be sensory. It doesn’t matter if the trees and plants grow in pots: they’re prized mainly for their changing colours. For the most part, cultural practices around nature – festivals, markets and other seasonal events – substitute for nature itself.

The Mori Building Company pioneered the Vertical Garden City concept with the opening of the Roppongi Ark Hills complex in 1986. A new kind of urbanism was emerging in which massive buildings, alone or as part of a group, stood apart from the fabric of the city and constructed their own reality. In his two-volume history of Tokyo completed in 1990, Edward Seidensticker notes this recent trend and observes that Ark Hills betrays “a certain want of integrity. It is concrete and pretends to be something else.”

During Japan’s asset price bubble of the late 1980s and early 1990s, founder and CEO Taikichiro Mori would briefly become the world’s richest man. When Mori died in 1993, the company passed to his son Minoru. It would go on to make many more additions to Tokyo’s artificial hillscape: Atago Green Hills (2001), Roppongi Hills (2003), Omotesando Hills (2006), Toranomon Hills (2014) and Azabudai Hills (2023). The family-run firm provides another defining characteristic of Tokyo: as long as scions of successful men remain dedicated to carrying out their ancestors’ visions, there will always be scope for projects of remarkable longevity.

Being a corporate urban planner means shouldering a terrible social responsibility. It requires great resolve. The subdivision of Tokyo into many small plots, pesky activists, recalcitrant homeowners, etcetera: all stand in the way of efforts to green the city. To help it understand the big picture, Mori Building Company keeps an enormous three-dimensional scale model of Tokyo at its offices on the 43rd floor of the Mori Tower in Roppongi Hills. This model includes every building in Tokyo and is constantly updated. Yes, it even includes your house. Who knows how often members of the Mori clan gather, shine a laser pointer on your building, and say things like “What’s his cholesterol level?” and “How many years has she got left?”

The Azabudai Hills project actually dates back to 1989. Under three different CEOs, the Mori Building Company spent 30 years negotiating with more than 300 property owners and lessees who occupied the site. These range from Japan Post, which became a partner in the development, to small businesses and individual homeowners. Construction work finally began in 2019. The architect responsible for the main tower, César Pelli, couldn’t make it to the grand opening in 2023 due to unforeseen circumstances. He died several years ago. You can infer that negotiations with some of the 300 occupants of the site reached a similar conclusion.

The centrepiece of the Vertical Garden City is the mixed-use skyscraper, the defining architectural expression of modern-day Tokyo. By stacking retail, office, hotel and residential space vertically, these towers promise to create open space at ground level. But that space is typically hostile to the street, demarcated by concrete steps, strategic greenery, and other features meant to discourage public use beyond the taking of a quick selfie. The Vertical Garden City stands in opposition to the dense and characterful neighbourhoods beloved by most Tokyoites.

The mixed-use skyscraper became ubiquitous in Tokyo not because people like it, but because it solves several problems at once. For the private development corporations and their corporate partners, it’s a way to create maximum business synergy from scarce land. For the major landowners, which are often religious organisations or former public utilities, it’s a way to earn sustainable revenue from the one resource that never goes out of fashion. But for the Metropolitan Government, it really is presented as a panacea for all ills, from lack of green space to disaster preparedness and a declining future tax base. The greatest act of showmanship of the Vertical Garden City has been to persuade city bureaucrats that it alone can attract high-net-worth foreign residents.

Nobody knows who these foreigners are that will only live in Tokyo if it becomes more like Singapore, but the message somehow stuck: Tokyo needed to up its skyscraper game. Floor Area Ratio (FAR) regulations once meant that high-rise towers could only be built on large open sites such as the west side of Shinjuku Station and reclaimed land in Tokyo Bay. The real march of the towers began in 2002, when FAR rules were relaxed as part of national policy to transform Tokyo into a globally competitive city. Private development corporations could now negotiate to build high on any site as long as they provided two things to the city: public space and green space.

These new Hills, Gardens, Plazas and Squares were never really intended to fool the people. There were just well-executed planning applications. New skyscrapers were likely to be approved if they promised an abundance of public space – even if it was mostly retail space. Meanwhile, green space could mean anything from Zelkova trees encased in concrete to a roped-off grassy mound. At developments like Azabudai Hills, great care goes into branding anything and everything as green space.

Corporate-led plazafication is not unique to Tokyo. Nor is the tendency of architectural plans to exaggerate how green a site will look. In architectural modelling software such as Autodesk, it’s as simple as selecting a species from a plant library and clicking where you want the trees to go. One-click greening is said to be so satisfying that it can be difficult to know when to stop. See a space, add a tree. Why not spray some over the rooftops? Dendromania – the manic compulsion to add trees – is an occupational hazard for architects of privately-owned public space worldwide.

Tokyo merely formalised all this to the extent that claims of green and public space became encoded in building names as standard. The Vertical Garden City is a fig leaf for compact urbanism, which in many ways is a good thing. Tokyo needs a variety of places to live – including for people who don’t much like Tokyo. What’s more, a certain talent for invention in the built environment began long before Tokyo got its Hills. It can even be traced back to the fujizuka, or Fuji mounds, the mini replicas of Mount Fuji that sprang up around Edo in the 18th Century.

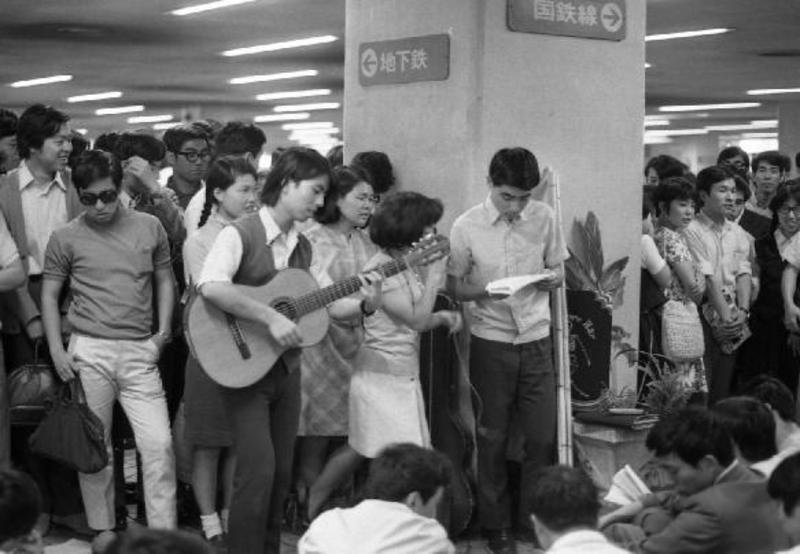

The real fissure in the relationship between place-naming and reality in Tokyo is said to have occurred at Shinjuku Station. In the summer of 1969, anti-Vietnam War demonstrations and counterculture rallies had been continuing for over a year in the plaza at the west exit. The protests were peaceful yet carnival and attracted thousands of students and workers. Tokyo Metropolitan Police had been unable to disperse the protests after a judge ruled that the name of the place, Shinjuku West Exit Underground Plaza, gave the public right of assembly. A novel solution was needed and was finally found by renaming it the Shinjuku West Exit Underground Passageway. Signs were changed overnight and the protestors removed the next day on the grounds of obstructing traffic.

The Shinjuku West Exit incident ushered in a new era in which simulation would be all the rage. The Metropolitan Government, anxious to avoid future appropriations of public space, was only too happy to cede urban planning decisions to the private sector. Citizens would be invited to assemble in new Plazas and Squares and enjoy a new form of communal expression called shopping. An impressive example of this can be found just around the corner at the south exit of Shinjuku Station. Takashimaya Times Square (1996) is a monumental building that seems designed to answer a single question: what if the great gathering place of the city was actually a department store?

Meanwhile, there’s been a new development at the west exit of Shinjuku Station. The old Odakyu department store (1967) recently closed for demolition. It will reopen as a mixed-use skyscraper, as yet unnamed, in 2029. I like to think that the name of the new building will have something to say about the protests that took place here 60 years earlier. Will it be a Plaza? Will it contain an antiwar message? Will it co-opt the idea of protest into a retail experience? My money’s on Shinjuku Peace Plaza.

But why all the interest in building names? Am I not just letting it be known, in that typically unassertive Tokyo way, that I’m a man with a certain sensitivity for the winds of change in naming? Whose talents might someday be directly applied in that illustrious field of real-estate branding which he pretends merely to observe from a critical distance? Who may already have the perfect name for that building you’d love to get started on, if only you had a name for it? No really, I wouldn’t even dream of putting myself forward. But wait, let me just show you my notebooks.

Architectural model of Tokyo: Antony Tran / World Bank Photo Collection. Shinjuku Station protests: historical / unknown.

Next: Utility Poles